This article demonstrates how to comply with the EU AI Act using Industry Frameworks.

The EU AI Act is no longer a future obligation. It is already in effect. Its scope reaches far beyond European borders. The regulation applies to any organization that places AI systems on the EU market, puts them into service within the Union, or uses them in ways that affect EU citizens. Location does not provide an exemption. If an AI system interacts with the EU market, the Act applies.

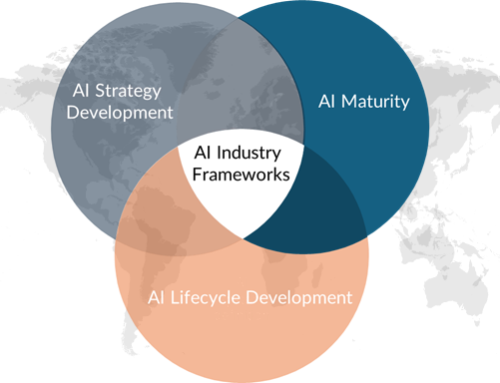

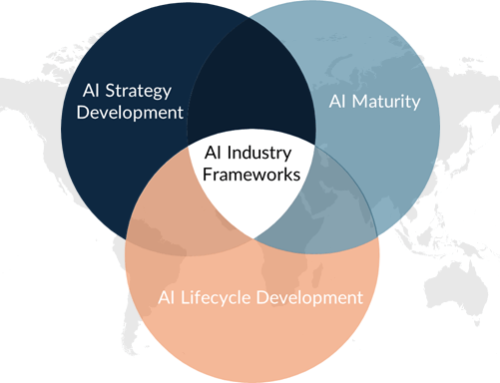

At the same time, organizations rarely start from scratch. Over the past years, many have adopted industry frameworks to structure responsible AI practices. Yet these frameworks differ in architecture, terminology, and emphasis—some focus on risk management, others on management systems, and others on internal governance principles. The landscape is rich, but fragmented.

This creates a practical tension. Legal obligations must be met. Internal governance must remain coherent. Duplicating structures would increase complexity rather than reduce it. Ignoring existing frameworks would waste valuable investments.

A more sustainable path emerges when organizations examine how regulatory requirements can be aligned with established best practices. This article explores that alignment by focusing on three influential reference points: the National Institute of Standards and Technology AI Risk Management Framework, ISO/IEC 42001, and the Microsoft Responsible AI framework.

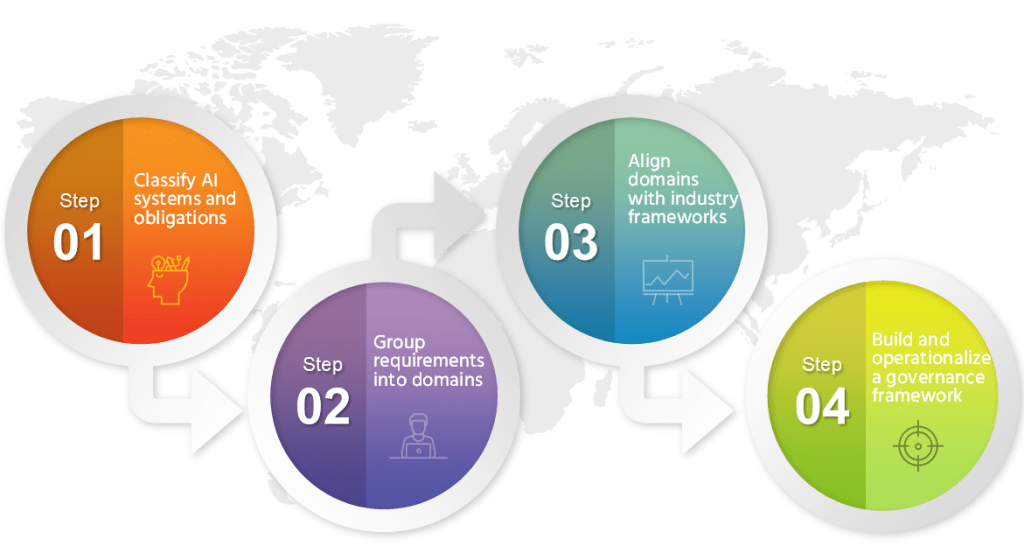

A Structured Approach to Complying with the EU AI Act

Complying with the EU AI Act becomes more manageable when approached as a structured sequence rather than a legal checklist. This article will elaborate on a simplified 4-step approach, shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: A simplified 4-step approach.

The process begins by classifying AI systems and identifying obligations. It continues by organizing regulatory requirements into logical domains. These domains can then be aligned with established industry frameworks. Finally, organizations can shape and operationalize an internal governance framework that transforms regulatory pressure into a structured, sustainable capability. Let’s start with Step 1.

Step 1. Classify AI Systems and Obligations

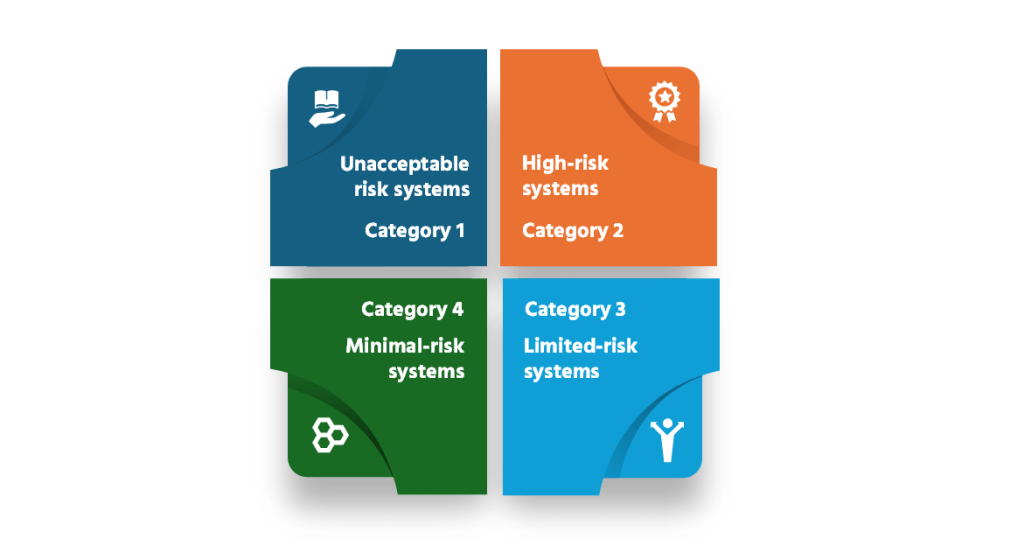

The EU AI Act structures obligations around four risk categories. Understanding these categories is the starting point for any compliance effort. The EU AI Act identifies four risk categories as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: AI system risk classification according to the EU AI Act.

Unacceptable risk systems are prohibited. These include AI practices that manipulate behavior, exploit vulnerabilities, or enable social scoring. Such systems cannot be placed on the EU market.

High-risk systems are permitted but subject to strict requirements. These typically include AI systems in critical infrastructure, employment decisions, creditworthiness assessments, law enforcement, migration control, and certain product-safety components. They must meet obligations related to risk management, data governance, technical documentation, transparency, human oversight, robustness, and conformity assessment.

Limited-risk systems are primarily subject to transparency obligations. Users must be informed when interacting with AI, including chatbots and synthetic content.

Minimal-risk systems face no additional regulatory requirements beyond existing legislation. Many routine AI applications fall into this category.

For an organization, classification does not occur automatically. It begins with establishing a structured AI system catalog. All AI systems must be identified, described, and documented, including their purpose, users, data inputs and outputs, and deployment context.

An internal classification process must then be formalized. Clear assessment criteria, defined responsibilities, and documented decision logic create consistency. Review mechanisms ensure that classification remains valid as systems evolve.

In the remainder of this article, the analysis uses a high-risk AI system as the reference point, as this category imposes the most comprehensive regulatory obligations and therefore illustrates the full compliance challenge.

Step 2. Group Requirements into Domains

Once a high-risk AI system has been identified under the EU AI Act, the legal obligations become more manageable when translated into three operational groups.

The first group covers risk management requirements. This part of the Act outlines a documented, continuous lifecycle process for identifying risks, evaluating impacts, selecting mitigations, and monitoring residual risk over time. The emphasis tends to fall on traceability of decisions, evidence of testing, and the ability to demonstrate control during changes and updates.

The second group covers data governance requirements, including the evidence trail around how data is selected, prepared, validated, and monitored for quality and relevance. This group also naturally includes technical documentation and record-keeping, as the Act requires a defensible “system file” linking data choices, model behavior, performance limits, and monitoring arrangements to the compliance evidence.

The third group captures the Act’s principle-like expectations for trustworthy, human-centric AI, referenced as seven guiding principles: human agency and oversight; technical robustness and safety; privacy and data governance; transparency; diversity, non-discrimination and fairness; societal and environmental well-being; and accountability. These principles help explain the “why” behind the control requirements, and they also provide a practical lens for aligning industry frameworks later in the article.

Step 3. Align Requirements Domains with Industry Frameworks

Before moving into detailed alignment, these domains can be treated as structured implementation steps. Each step can then be assessed against relevant industry frameworks to determine how existing practices align with EU AI Act obligations and where targeted adaptations are required.

3.1 Embedding the AI Risk Management into the Enterprise Risk Management Framework

The first analytical move does not begin with building something new. It begins with examining what already exists. Most medium and large organizations operate an enterprise risk management framework. That framework defines how risks are identified, assessed, escalated, monitored, and reported across the organization.

When a high-risk AI system falls under the EU AI Act, the regulatory risk management obligations should not remain isolated within a technical team. They can be embedded into the existing enterprise structure.

The National Institute of Standards and Technology AI Risk Management Framework (AI RMF 1.0) provides a practical bridge. Its structure revolves around four core functions: Govern, Map, Measure, and Manage. “Govern” establishes policies, accountability, and oversight structures. “Map” defines context, intended use, and impact boundaries. “Measure” evaluates risks and performance characteristics. “Manage” focuses on mitigation, response, and continuous improvement.

This structure aligns naturally with the EU AI Act’s lifecycle-oriented risk requirements. The Act requires ongoing risk identification and mitigation, not a one-time assessment. By integrating AI-specific risk registers, impact criteria, and monitoring indicators into the enterprise risk framework, organizations avoid parallel compliance silos.

In practice, AI risks become part of the enterprise risk taxonomy. Escalation paths remain consistent. Oversight bodies retain visibility. Regulatory obligations are therefore absorbed into the organization’s existing risk architecture rather than layered on top of it.

Beyond enterprise risk integration, two additional domains must be addressed in parallel: governance-related requirements and guiding principles. They are presented separately for analytical clarity, yet they inevitably overlap in practice.

The overlap arises because operational obligations are designed to give effect to broader normative expectations. What is articulated at the level of principle often reappears as concrete documentation, control, or oversight requirements. Treating them as distinct layers helps structure the analysis. Recognizing their connection ensures that compliance efforts remain coherent rather than fragmented.

3.2. Complying with Data and AI Governance Requirements

For high-risk AI systems, the EU AI Act establishes specific data governance obligations.

Organizations must implement documented data governance and management practices for training, validation, and testing datasets. Data must be relevant to the intended purpose and sufficiently representative of the context in which the system will be used.

Datasets must be sufficiently free of errors and complete, taking into account the system’s purpose. Where appropriate, potential biases must be identified and mitigated.

The Act also requires documentation of data sources, collection processes, preparation methods, and assumptions, as well as record-keeping and logging to ensure traceability.

These requirements form the data governance backbone for high-risk AI systems.

3.3. Complying with Guiding Principles under the EU AI Act

In addition to binding obligations, the EU AI Act sets out guiding principles for trustworthy, human-centric AI.

These principles include human agency and oversight; technical robustness and safety; privacy and data governance; transparency; diversity, non-discrimination, and fairness; societal and environmental well-being; and accountability.

While not structured as operational controls, these principles inform how requirements are interpreted and implemented. They provide the normative foundation against which governance arrangements and technical measures are assessed.

Together, they frame the broader expectations that high-risk AI systems must meet beyond procedural compliance.

In the following section, the governance requirements outlined in 3.2 and the guiding principles described in 3.3 are combined and translated into a structured approach for compliance through industry frameworks.

3.4. Operationalizing EU AI Act Regulatory Obligations with Industry Frameworks

3.4.1. Assessing Data and AI Governance Maturity

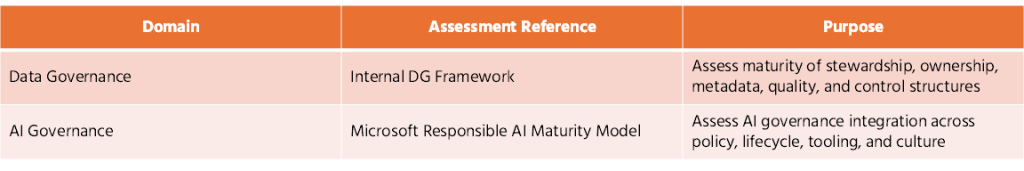

Before aligning regulatory requirements, organizations need clarity about their current governance maturity. Table 1 summarizes the recommended approaches.

Table 1: An approach to measuring data and AI governance maturity.

Data governance maturity is assessed using the organization’s existing internal DG framework. This establishes whether ownership structures, lifecycle controls, and documentation processes are sufficiently institutionalized.

For AI governance, the Microsoft Responsible AI maturity model provides a structured lens. It evaluates governance across leadership commitment, risk processes, policy embedding, technical controls, and operational integration. Maturity levels typically evolve from ad-hoc experimentation to enterprise-wide institutionalization.

This dual assessment clarifies structural readiness before regulatory mapping begins.

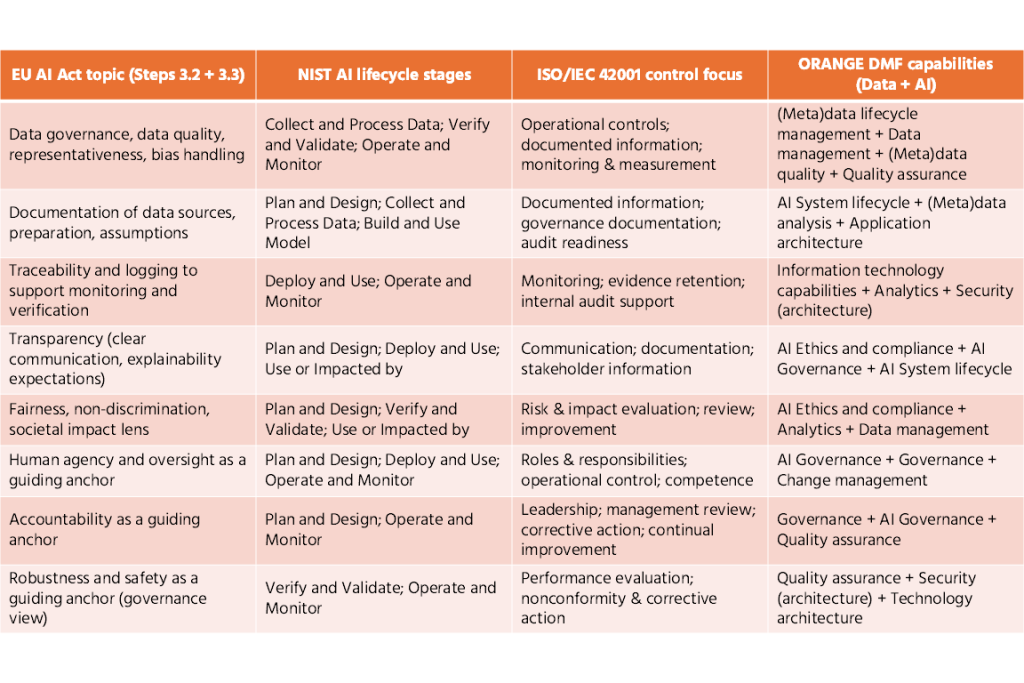

3.4.2 Mapping the EU AI Act Governance Requirements and Principles to Industry Frameworks

This mapping combines the data-governance requirements (3.2) and the guiding principles (3.3) into one integrated layer. Each EU AI Act topic is then mapped to the NIST AI lifecycle stages (so obligations are covered end-to-end), linked to ISO/IEC 42001 control themes (so the work becomes auditable and repeatable), and finally anchored in the O.R.A.N.G.E. DMF data and AI capability map (so accountability sits in the operating model).

Table 2 presents the mapping results.

Table 2: Mapping the EU AI Act Governance Requirements and Principles to Industry Frameworks.

The mapping highlights a structural insight: EU AI Act obligations are not isolated legal clauses. They distribute naturally across the AI system lifecycle, the management system layer, and the enterprise capability architecture.

When aligned with the NIST AI lifecycle model, governance requirements and principles appear at distinct but connected stages. Data governance obligations cluster around Plan and Design, Collect and Process Data, and Verify and Validate, because representativeness, quality, and bias must be addressed before and during model development. Transparency, oversight, and accountability extend into Deploy, Use, Operate, and Monitor, where real-world impacts become visible. Fairness and societal considerations reach into the final stage, Use or Impacted by, emphasizing that compliance does not end at deployment.

ISO/IEC 42001 adds structural consistency. It transforms lifecycle activities into controlled processes by requiring documented information, defined responsibilities, monitoring, internal review, and continual improvement. This prevents governance from remaining informal or project-based.

Step 4. Build and Operationalize the Internal Data and AI Governance Framework

Once regulatory requirements have been mapped to lifecycle stages, ISO controls, and ORANGE DMF capabilities, the final step is structural integration. The organization consolidates these elements into a coherent internal framework that defines accountability, embeds controls into processes, and ensures continuous monitoring.

At this stage, compliance is no longer treated as a regulatory add-on. Risk management, data governance, oversight mechanisms, and monitoring processes become integrated into existing governance structures and AI lifecycle activities. Documentation, review cycles, and performance evaluations become routine practice.

The practical structuring of such an integrated approach is demonstrated in my book, Aligning Data and AI Governance, which details the alignment between data and AI governance. Courses at the Data Crossroads Academy further illustrate how this integration can be implemented within enterprise environments.

The outcome is a governance architecture in which EU AI Act obligations are absorbed into the operating model, supported by clear capability ownership and continuous improvement.